It was a Saturday morning, and my daughter had been awake for forty-five minutes. By that point she had already peppered me with questions about what family birthdays are in which month, fourteen pieces of Star Wars minutiae, and three requests to look at her baby pictures. That’s when Dena texted from upstairs that our son was awake and needed his diaper changed.

Somewhere between closing the snaps on his pajamas and heading back downstairs to start toasting bagels, I looked over my to-do list. That’s when I had The Thought:

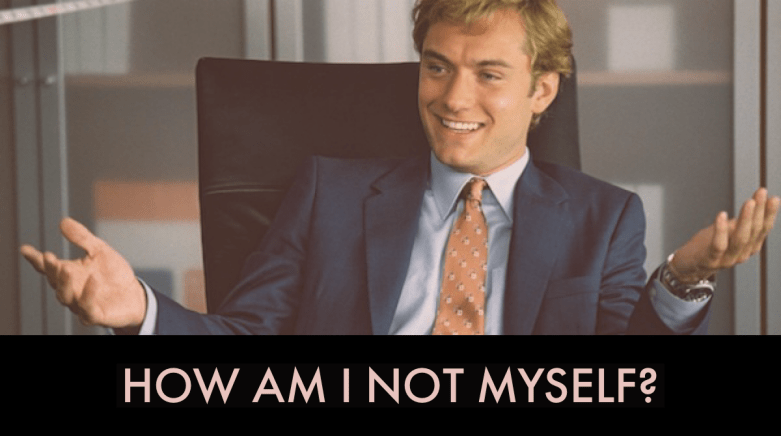

“It’s 8 a.m., and the productive part of my day was over an hour ago.”

A few months ago, this thought would’ve locked me in for (to paraphrase the words of The West Wing’s Charlie Young) a “low self-image day.” That to-do list would’ve been set aside, and lethargy would have taken over.

But not this day. This day I thought about the difference between the current mental conditions and the mental forecast.

Even if you hyper-schedule your day, you still don’t know exactly how you’re going to feel a few hours from now, or if the reality of your day is going to match your plan. Unless, that is, you decide that your interpretation of your current mental state and the outside forces acting on it are a prediction of what’s to come, and you live out your self-fulfilling prophecy.

At any given point, our mood is a snapshot of the current conditions. It’s useless, at best, to assume that how you feel now is how you will feel in the future.

Like any good forecast, you need to look at other conditions that hold influence over you.

Because unlike the weather, you have options to head off a storm front moving in inside your head. You need to be able to take that moment to step back and clearly see what you’re looking at when you look at your mental state.

This isn’t just for people with depression. Every person makes predictions about what might happen in the future, but the only information we have is what we can see and hear in the present. Any person might make a bad prediction. While my depression doesn’t create a unique problem in that sense, it does make it harder to differentiate between the current conditions and the forecast.

But I’m learning.

I ate my bagel. Had some coffee. Washed some dishes. Gave my son a bath. Wrote the first draft of this post, and got a lot of other boxes checked off in my to-do list.

And a big part of why the day didn’t stop at 8 a.m. was because I’m learning to be a better emotional meteorologist.

You must be logged in to post a comment.