Watching this film for the first time with my dad was a big moment. At first, I didn’t appreciate how unique this horror film was for featuring a black man as the lead. I wasn’t thinking about the social commentary being made by the way he takes control of the survival plan and the narrative itself. But then comes the film’s shocking ending and it was time for father and son to talk about the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

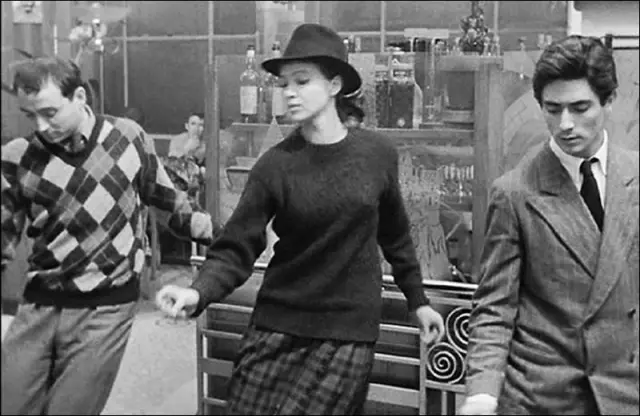

This is a film made with the slimmest of shoestring budgets. And yet, this movie is the genesis point of so much of the zombie horror subgenre.

It has a lot to do with Duane Jones. His Ben survives a horde of zombies only to be slain in the final reel. As he emerges from the house he hid in through the night, a random deputized man with a rifle fires, ending his story.

In a contained space, for one night, a black man held tenuous power and influence, and took on the heroic role as all the white people around him crumbled from fear, prejudice, and ego. But none of that mattered when trying to carry his heroic self back out into the wider world, where agents of the law can’t (or can’t be bothered to) tell the difference between a black man and a supernatural threat.

Even if it may not have been Romero’s intent to include this subtext in the film, he ran with the idea in future films. It’s a trope of zombie films that the audience should understand that There’s An Allegory Going On.

You must be logged in to post a comment.